EVENING GROSBEAK (COCCOTHRAUSTES VESPERTINUS)

Evening Grosbeaks are striking when seen up close. Besides being rather stocky, and with massive pale greenish-yellow beaks, their plumage is a patchwork of contrasting whites, yellows, grays, blacks, and shades of brown. Definitely, they are birds not to be forgotten! They are quite social too, especially in winter and spring, when flocks of a hundred or more may appear at bird feeders. However, Evening Grosbeaks tend to be secretive during summer, breeding in mixed conifer forests and often building flimsy nests high in tall conifers, which makes them difficult to observe. Other than a multiyear study in Colorado in the 1980s, much of what is known about the species’ breeding biology is derived from opportunistic encounters and studies of breeding bird communities of which they are members (Gillihan and Byers 2020). Montana is no exception. The first nest was not found until 1952 near Bozeman (Davis 1953), and fewer than 10 nests have been reported since then, the majority during a study of coniferous forest birds at Lubrecht Experimental Forest east of Missoula (Manuwal 1968). Moreover, the only Montana nest studied in detail, and then only during incubation, was near Missoula in 2018 (Hendricks 2021). Much remains to be learned about their lives in Montana and elsewhere.

Continent-wide summer and winter surveys indicate that Evening Grosbeaks are in trouble. Those of us living in western Montana may scoff at this notion. After all, their calls can be heard without much effort most any spring and summer day, and small flocks are often encountered in riparian and mixed conifer woodlands. And, the species continues to show up at urban feeding stations during winter and spring. Nevertheless, in recent years the Evening Grosbeak has become a sort of “poster child” for the declines reported among populations of many North American birds (Rosenberg et al. 2019). Its image appears on the cover of the 2016 Revisions for the Partners in Flight Conservation Plan in which it is included on the Yellow Watch List (Rosenberg et al. 2016). More recently, it is listed as a species of Continental Concern (USFWS 2021) and among the 70 “tipping point species” in North America (NABCI 2022); i.e., those having experienced a decline in global numbers exceeding 50% between 1970 and 2019, and projected to lose another 50% of the population in the next 50 years if nothing changes.

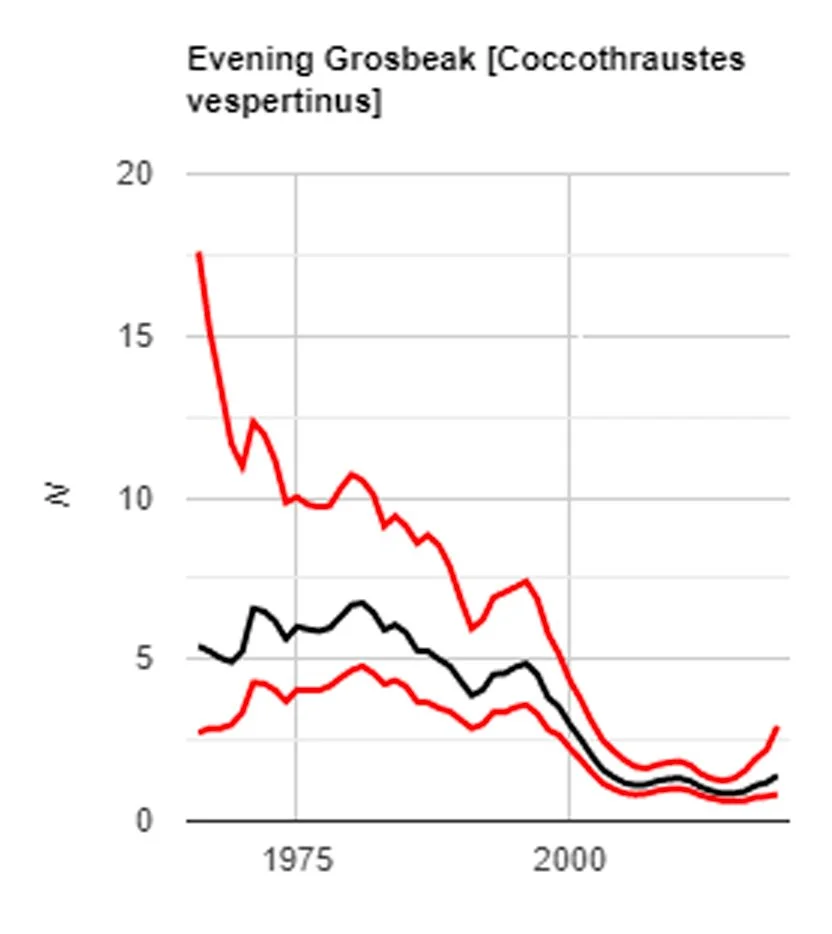

All trends tell this alarming story. Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) data for 1966–2019 (Fig. 1) indicate declines of 2.5% per year survey-wide, 2.8% per year for the US and Canada, 1.8% per year for the Northern Rockies Bird Conservation Region (BCR 10), and 1.4% per year for Montana. The 2014 population estimate for Evening Grosbeak north of Mexico was 3,400,000 individuals, with a population decline of 94% from 1970 to 2014 and a projected half-life (the period required to lose half of the remaining population) of 38 years (Rosenberg et al. 2016). An analysis of data from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Project Feeder Watch for 1989 to 2006 revealed that mean flock size of Evening Grosbeaks visiting feeders during winter, and the number of feeding stations reporting their visitations, declined by 27% and 50%, respectively, with declines exceeding 50% of reporting stations in parts of the Mountain West, Pacific Northwest, and northeastern North America (Bonter and Harvey 2008). No feeding stations with long-term data reported increases in mean flock size. More recently, population trajectories derived from analysis of eBird data are consistent with other monitoring schemes and show significant declines of Evening Grosbeaks in spring, fall, and winter (Walker and Taylor 2020). The same pattern is also reflected at local sites, such as the Oregon State University campus in Corvallis, where numbers of Evening Grosbeaks pausing in spring since the 1970s have declined by approximately 2.6% per year (Robinson et al. 2022), which is similar to the continental trend.

One of the earliest conclusions about Evening Grosbeaks (at a time when the nest was still unknown) was that they were not true migrants but better considered wanderers or nomads (Coues 1879). They were considered birds of the Mountain West and western Canada until the latter decades of the 19th century, rarely appearing east of the upper Midwest, and then only as winter visitors during invasion years. Beginning in the early 20th century, winter invasions in the east became more frequent, more widespread, and penetrated farther south (irregularly to the Gulf Coast states), breeding was first documented throughout the southern parts of eastern Canada and adjacent US, occasionally as far south as Connecticut but regularly in New England and northern New York (Gillihan and Byers 2020). Thus, the species’ nomadic behavior might lead to a perceived decline in the global population because the birds move about in unpredictable ways, whereas most traditional monitoring schemes (BBS, CBC, Project Feeder Watch) remain stationary. However, consistency of recent eBird data (Walker and Taylor 2020), which is not stationary, with that gathered from other monitoring efforts (Bonter and Harvey 2008, Rosenberg at al. 2016), support the conclusion that the decline, especially since 1970, is real and widespread.

So, why are Evening Grosbeaks nomadic? Anecdotal reports indicated that their winter wanderings were tied to food supply (Coues 1879), the birds often feeding then and during spring on the seeds and buds of a variety of deciduous tree species (especially maples and elms) and seeds of pines, species whose seed crops fluctuate among years. CBC data have since been used to document in more detail the patterns in Evening Grosbeak irruptions, linking them to food availability. Irruptions may occur in western North America, as they do in the east, but the magnitude is often lower. Other differences between events in eastern and western North America are evident. Grosbeaks may remain abundant in the west during years when few birds are noted in the east, and irruptions in the west do not always occur during years when they do elsewhere (Bock and Lepthien 1976). However, seed-crop failure among many boreal tree species at the same time leads to wanderings by Evening Grosbeaks across a broad front. More specifically, winter irruptions in both the east and west are related to production of large seed crops in montane and boreal conifers (especially pines) the year prior to one of poor production (Koenig and Knops 2001), with irruptions often synchronized then across the entire range (Koenig 2001). However, analyses using BBS data indicate winter irruptions do not appear to be strongly correlated with breeding densities of grosbeaks.

Evening Grosbeak invasions also occur in response to foods other than cone or deciduous seed crops. Notably, the species is attracted to infestations of spruce budworms (Choristoneura fumiferana) in spring and summer, when flocks and breeding adults feed on budworm larvae and pupae (Gillihan and Byers 2020). CBC data from the Great Lakes region, New England, and eastern Canada during 1940 to the early 2000s linked fluctuations in Evening Grosbeak presence to the massive 1970s budworm infestation, with >90% of counts reporting grosbeaks in the 1970s and 1980s for all three regions before declining to as few as 25% of counts by 2000, when the budworm infestation was well past its peak (Bolgiano 2004). In general, Evening Grosbeaks in eastern North America show a positive numerical response to increasing budworm numbers (Vernier and Holmes 2010). Interactions between grosbeaks and spruce budworm infestations in western North America have received much less study. Nevertheless, Evening Grosbeaks in the west are drawn to budworm infestations during the breeding season, including in Montana, and their influence on budworm numbers can be significant. At two sites in Washington state, for example, individual grosbeaks were estimated to have eaten an average of 12,600 to 26,400 larvae, for a total of 3,036,000 and 8,900,000 larvae consumed by all grosbeaks at the respective sites (Takekawa and Garton 1984). This was determined to be equal to a cost savings (1980s dollars) of $22,750 to $34,125 per km2 in insecticide spraying.

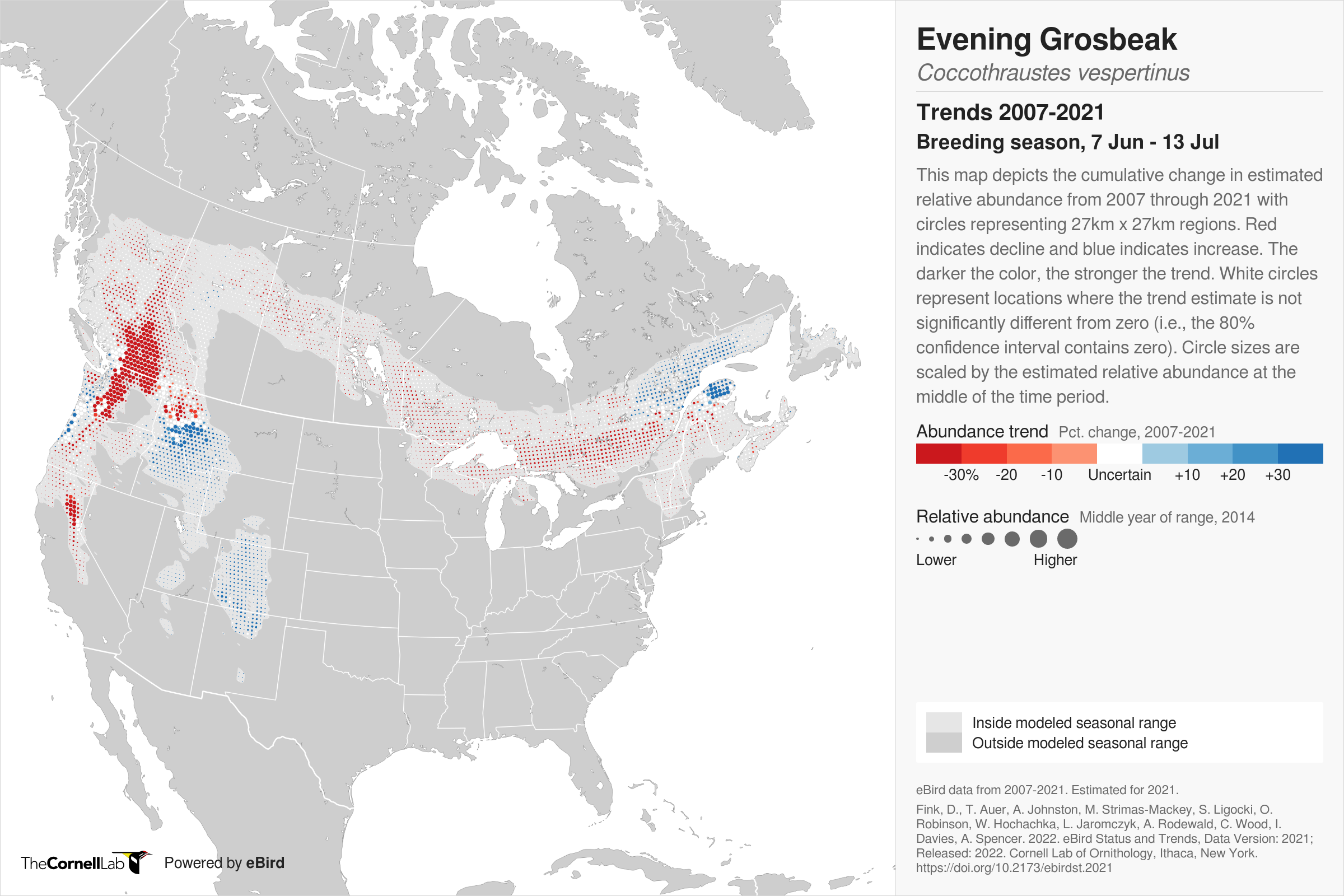

So, we know Evening Grosbeaks tend to be nomadic, and we have pretty good evidence that populations are in steep decline. But what is causing the decline? Several explanations have been proposed, although it is not yet clear which are most significant, and some probably are interacting. The driver of Evening Grosbeak nomadism, fluctuations in food supply, likely is involved in the declines, and habitat change could affect food availability for grosbeaks throughout the year (Gillahan and Byers 2020); change in habitat quality may be a result of effective budworm control. Conversely, climate change could affect a number of factors, including persistent budworm defoliation and consequent tree mortality, wildland fire frequency, resultant logging (including post-fire salvage logging), succession and change in forest composition, fluctuations in parasites and disease, and snow-cover dynamics, all of which could affect grosbeak numbers and movements (Bonter and Harvey 2008, Venier and Holmes 2010, Robinson et al 2022, Keyser et al. 2023). Use of aerial insecticides to control budworm infestations could contribute to grosbeak mortality (Finley 1965), but spraying has not always been shown to have adverse effects on grosbeak numbers (Blais and Parker 1964). Determining the main drivers of Evening Grosbeak declines from all of the possibilities will be challenging. Worth noting, perhaps, is that grosbeak declines, although widespread and steep, are not yet universal (Fig. 2). One of the few regions where Evening Grosbeaks appeared to increase during 2007–2021 in the breeding season was part of western Montana and adjacent Idaho, perhaps (sadly) their Last Best Place in the west, but maybe where we can find clarity through focused study that will lead to management solutions that halt or reverse the declines elsewhere.

Literature Cited

Blais, J. R., and G. H. Parker. 1964. Interaction of Evening Grosbeak (Hesperiphona vespertina) and spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana (Clem.)) in a localized budworm outbreak treated with DDT in Quebec. Canadian Journal of Zoology 42: 1017-1024.

Bock, C. E., and L. W. Lepthien. 1976. Synchronous eruptions of boreal seed-eating birds. American Naturalist 110: 559-571.

Bolgiano, N. C. 2004. Cause and effect: changes in boreal bird irruptions in eastern North America relative to the 1970s spruce budworm infestation. American Birds 58: 26-33.

Bonter, D. N., and M. G. Harvey. 2008. Winter survey data reveal rangewide decline in Evening Grosbeak populations. Condor 110: 376-381.

Coues, E. 1879. History of the Evening Grosbeak. Bulletin of the Nuttall Ornithological Club 4: 65-75.

Davis, C. V. 1953. Evening Grosbeak nesting in Montana. Wilson Bulletin 65: 42.

Finley, R. B., Jr. 1965. Adverse effects on birds of phosphamidon applied to a Montana forest. Journal of Wildlife Management 29: 580-591.

Gillahan, S. W., and B. Byers. 2020. Evening Grosbeak (Coccothraustes vespertinus) version 1.0. In: Birds of the World (A. Poole and F. Gill, editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY.

Hendricks, P. 2021. On the incubation behavior of Evening Grosbeaks (Coccothraustes vespertinus). Wilson Journal of Ornithology 133: 295-299.

Keyser, S. R., D. Fink, D. Gudex-Cross, V. C. Radeloff, J. N. Pauli, and B. Zuckerberg. 2023. Snow cover dynamics: An overlooked yet important feature of winter bird occurrence across the United States. Ecography 2023: e06378.

Koenig, W. A. 2001. Synchrony and periodicity of eruptions by boreal birds. Condor 103: 725-735.

Koenig, W. A., and J. M. H. Knops. 2001. Seed-crop size and eruptions of North American boreal seed-eating birds. Journal of Animal Ecology 70: 609-620.

Manuwal, D. A. 1968. Breeding bird populations in coniferous forests of western Montana. M.S. thesis, University of Montana, Missoula.

NABCI (North American Bird Conservation Initiative). 2022. The state of the birds, United States of America, 2022.

Robinson, W. D., J. Greer, J. Masseloux, T. A. Hallman, and J. R. Curtis. 2022. Dramatic declines of Evening Grosbeak numbers at a spring migration stop-over site. Diversity 14: 496. https://doi.org/10.3390/d14060496.

Rosenberg, K. V., A. M. Dokter, P. J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A. C. Smith, P. A. Smith, J. C. Stanton, A. Panjabl, L. Helft, M. Parr, and P. P. Marra. 2019. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 133: 120-124.

Rosenberg, K. V., J. A. Kennedy, R. Dettmers, and 21 others. 2016. Partners in Flight Landbird Conservation Plan: 2016 revision for Canada and continental United States. PIF Science Committee.

Takekawa, J. Y., and E. O. Garton. 1984. How much is an Evening Grosbeak worth? Journal of Forestry 82: 426-428.

USFWS (U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service). 2021. Birds of conservation concern 2021. United States Department of the Interior, U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Migratory Birds, Falls Church, Virginia.

Venier, L. A., and S. B. Holmes. 2010. A review of the interaction between forest birds and eastern spruce budworm. Environmental Reviews 18: 191-207.

Walker, J., and P. D. Taylor. 2020. Evaluating the efficacy of eBird data for modeling historical population trajectories of North American birds and for monitoring populations of boreal and Arctic breeding species. Avian Conservation and Ecology 15: 10. https://doi.org/10.5751/ACE-01671-150210

(Bob Martinka photo)

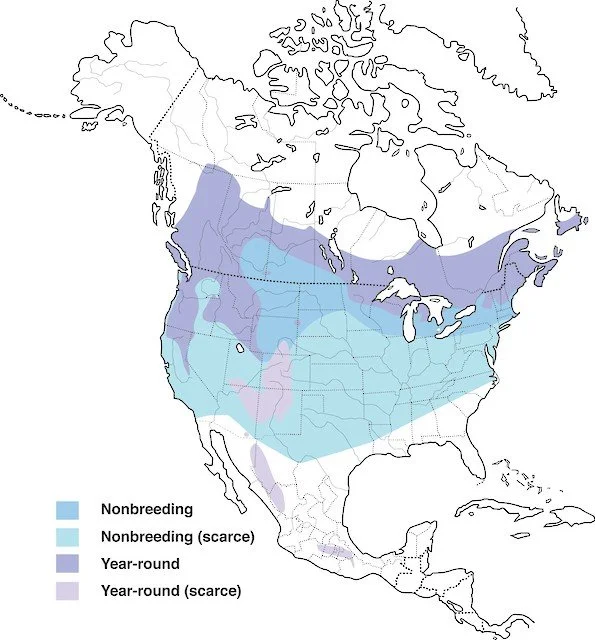

Distribution of the Evening Grosbeak (courtesy of Cornell Lab of Ornithology)

(Bob Martinka photo)

Figure 1. Continental BBS trend, with 95% confidence intervals, for Evening Grosbeaks from 1966 to 2019. Y axis is relative abundance per route.

(Bob Martinka photo)

Figure 2. Change in relative abundance of Evening Grosbeaks for 2007-2021 during the breeding season, based on eBird data.